I’m not much of a golfer. In fact, when I’m asked if I play, I reply that golf gave up on me years ago. I appreciate the beauty of the game and the finesse that great players demonstrate, but my golf game required a great number of “Mulligans” for me to finish a round.

There are some parallels between golf and estate planning, especially as it pertains to errant strokes and missed opportunities that inevitably occur in golf and sometimes, in estate planning.

To be clear from the outset, trust modifications aren’t necessarily the result of a “poor shot” or client/attorney error. For example, keeping with the golf analogy, many clients may have carefully chosen their clubs, selected a caddy, settled on a game plan and started out on the course. Then, midway through the game, the rules change. That is certainly the case with the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA). When ATRA was enacted, many of the most foundational rules of the game got changed.: a new “sand trap” here, a “water hazard” there, and maybe a pin or two has been moved. Consequently, the clubs, tools and “game strategy” these players originally chose must now be adapted to fit the new rules of the game.

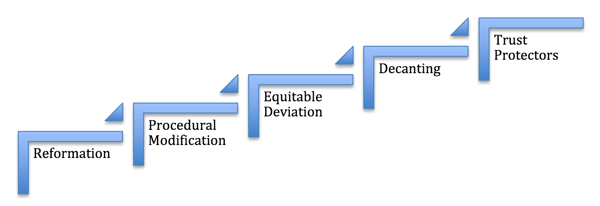

Fortunately for estate planning professionals (and for poor golfers like me!) there are modification options (mulligans or do-overs) to get things back on track. These options range from the mundane to the exotic and complex. In ascending order they are:

Among the simpler options are: Reformation, Procedural Modification and Equitable Deviation. In this blog, I’ll focus on these first three. In two future blogs I’ll be addressing the last two, trust decanting and modification by trust protectors.

Reformation. At the most basic end of the modification spectrum is trust reformation. Essentially, trust reformation deals with the process of correcting scrivener’s errors or other patent errors when the trust document fails to accurately reflect the actual original intent of the settlor. Central to the purpose of reformation is that the governing document does not accurately reflect what the settlor actually intended at the time the document was executed. Important note: If the document and strategy must change due to new circumstances, new opportunities under the law or because the settlor’s intentions have changed after the fact, other modification options (higher on our modification hierarchy) must be considered.

Procedural Modification. Most states provide a statutory mechanism for procedural modification of an irrevocable trust, allowing changes to be made to meet the settlor’s tax-saving objectives so long as the resulting trust terms – especially the dispositive provisions – remain consistent with the settlor’s probable intent at the time the trust was initially established. Stated another way, procedural modification contemplates a modest departure from the settlor’s original intent because more substantive tax-oriented changes are being made to the underlying strategy.

This approach provides an alternative when the results intended by the plan cannot be successfully achieved as the plan is originally established. Modification actions are often brought to adjust provisions concerning trust administration – “fine-tuning” the trust to reduce the impact of taxes.

Equitable Deviation. Under the doctrine of equitable deviation a court may make changes in important provisions in the trust upon a showing of unforeseen – and unforeseeable – changes in circumstance, even when the impact of those changes may frustrate one or more of the settlor’s main objectives when establishing the trust. The test is whether, if the client knew then what the client knows now, he or she would have done some things differently.

Bear in mind that where courts are involved, modifications can be time-consuming and costly. This is due in part to the fact that few judges come with much experience in estate planning and trust administration matters. Because they are not experts, they are often reluctant to make significant changes to an irrevocable trust. The wiser approach may be to do some level of procedural modification and ask the court to simply add a decanting provision to the trust, a more complex but more creative and flexible alternative, which I’ll be addressing in a future blog.

Important note: In September, as part of our Continuing Legal Education curriculum, Wealth Counsel will offer an in-depth, multi-day course on “Modification Options for Irrevocable Trusts.” Take advantage of this opportunity to update yourself on the law and the various trust modification options available.

Are you using reformation, procedural modification, and/or equitable deviation in your practice? Please tell us why (or why not) and share any insights you might have in our comments section.